In 2020 Mr. Torchinsky bought a small Chinese electric vehicle called the Changli from China. This made him famous there; he is featured in a promotional video, on the company’s Alibaba pages, and in the Chinese news here, here, here, here, and here. Let’s do a deep-dive into the Changli and other vehicles like it.

In China, a vehicle like this is generally categorized as a Low Speed Electric Vehicle (LSEV). As the name implies, this category only covers electric cars. But the LSEV sector originates from gas powered vehicles of the same size and kind. Originally, these vehicles were intended for the elderly, those with disabilities, and for local business in smaller cities and villages.

Electrification Brought A Boom In LSEVs

The sector was ridiculed quite a lot in China for poor quality, ancient technology, and weird looks. However, things started to change when the sector grabbed the opportunities offered by electrification. Suddenly, powertrains became smaller and more reliable, leaving more space for passengers, more leeway to add luxuries, and more freedom of design.

This change started early, long before carmakers began their road to electrification. The earliest LSEVs appeared in the early 2000s. For a while, most manufacturers produced a mix of electric and gasoline powered cars, but nowadays the vast majority is EV-only.

LSEV isn’t strictly defined, though an often-used definition is: LSEV mainly refers to three- and four-wheeled electric vehicles with low driving speed; short driving range; and technological simplicity, specifically when it comes to batteries and motors. Maximum speed is 70-80km/h, but most LSEVs are way slower.

With electrification, the cars became more attractive for a wider audience. Families and even young professionals started to get interested, considering the LSEV as an alternative to an electric scooter or 3-wheeler. At the same time, China’s home-delivery secor started its app-fuelled boom, which, combined with stricter emissions regulations in big cities, led to an increasing demand for small electric delivery vehicles.

Gold on the horizon! As always, the manufacturers responded quickly, adding, in no time, dozens and dozens of new body styles, designs, and specialty vehicles. They were greatly aided by the relative simplicity of an EV platform compared to an ICE platform. The small electric motor can be fitted front, middle, or rear, depending where you want it. That done, you can basically add any body on top. Originally, the gasoline cars looked like odd little hatchback wagons, and there wasn’t much variation. Now, with booming demand and the EV platform, the number of variants has exploded.

Suddenly, there were 4-wheel sedans, SUV-style cars, three or four-wheel pickup trucks with a single or a double cab, sports cars, convertibles, long-wheelbase tourism cars, off-road cars, small trucks, smaller trucks, tiny trucks, and so much more. The variation is endless and utterly fascinating. For a while, it seemed the boom would never end.

How many LSEVs roam the Chinese roads is anybody’s guess. In 2020, a government report estimated the number at 10 million plus, but I think that’s on the very low side. The same report counted about 100 manufacturers with an annual production capacity of 2 million vehicles. The latter seems about right, the former way too low.

The Feds Have Been Trying To Regulate LSEVs, Cities Do Dog-And-Pony Shows To Avoid It

But for a while, there have been some dark clouds on the horizon. Happily, those clouds don’t ever get much closer but they are there, constantly threatening the sector. The clouds are of the regulatory kind. For many years, the central Chinese government in Beijing has tried to rule in the somewhat lawless sector, citing safety and congestion reasons. But in China, the responsibility of regulating LSEV cars, and also scooters and bicycles, lies with local city governments. And they have less interest in bothering the sector, fearing that would antagonize business and consumers alike. And any ban would hurt the cities themself as well, as local governments use LSEVs for all kinds of official duties, from policing to collecting garbage.

A vague compromise exists, whereby cities crack down on LSEVs now and then, in highly publicized police actions, to satisfy demands from higher above. But after a few weeks, everything goes back to normal. Also, when there is a large gathering in a city, LSEVs are sometimes temporarily banned from the streets until the gathering is over.

So for now the sector seems safe albeit in an unbalanced manner. Perhaps it would be better for all when there was some form of national regulation for LSEVs. It would make the companies and owners safer from government crackdowns, and it would help the government reach its goals on road safety and against congestion. But none of that is likely to happen anytime soon.

At any provincial LSEV show, there are at least a hundred manufacturers present; I estimate the total closer to 1,000. But I guess it depends on if you count only officially registered manufacturers or every shed that turns out a few dozen cars per year.

Safety Concerns

Safety is a real problem. Every day there are stories of nasty accidents with LSEVs in the Chinese media. I once saw a 3-wheel car tipping over in Beijing when it went through a corner. Numbers on traffic deaths are hard to find in China. The most recent report I could find was a 2018 government publication citing 830,000 accidents resulting in 18,000 deaths and 186,000 injuries from 2013 to 2018.

A connected problem is insurance. Due to the legal uncertainty, most insurance companies refuse to insure LSEVs. This, however, doesn’t really hurt sales, as most Chinese consumers wouldn’t even insure their car if they didn’t have to. And LSEVs are cheap, so one may calculate that buying a new one is cheaper than paying insurance.

At this moment, as they are regulated at a local level, rules for LSEVs may differ per city, village, and even per city district. In Beijing for example, where I lived for many years, LSEVs are generally not allowed within the Fifth Ring Road. In the past, they were allowed basically everywhere. But there are still exceptions for elderly, those with disabilities, and delivery services.

Copyright issues

The fact that many LSEV makers borrowed design elements from foreign brands is well-documented by now, so I’ll leave that with the Dayangchok G, which looks a little bit too much like a Suzuki Jimny. But there are more, of course. Since Chinese car design has become more original in recent years, LSEV makers have started to copy Chinese brands. One might call that a positive development: Chinese design is finally good enough for those critical LSEV folks. So instead of copying a Suzuki Jimny they’ve gone to copying Hongqi’s and ORA’s.

Mostly it is just the grille, though sometimes they copy the entire front, and sometimes the entire look and feel of a car. It is pretty smart work. Copying a car into a smaller scale isn’t that easy, and the detailing is impressive. For example, the odd triangular shapes in the bumper of the Cyberster clone are a 1:1 copy of the original.

But happily, not all design is copy-cat. Some LSEV makers really try to be original. That doesn’t always work, but to try is better than not to try. Right?

These are just four examples, but they show the many different directions LSEV design is going: from a streamlined one-seater to an experimental four seater to a long-wheelbase triple-cabin pickup truck to a “cute” car likely designed for ladies. It is all happening, and I truly believe that one day one of these LSEV designers will come up with something beautiful.

[Editor’s note: That fake Mercedes on the top right is epic! Also, as a reader wanted me to make clear, technically these vehicles aren’t infringing upon “copyrights” — this is an issue of trade dress/trademarks/IP. -DT]

Changli

Now to Mr. Torchinsky’s car. “Changli” is the brand name. The full name of the company is Changzhou Changli Vehicle Factory. As with so many Chinese manufacturers, the city where the company is based is part of the name. In this case that is Changzhou, a city of some 5.2 million in China’s Jiangsu Province, about 125 miles up the Yangtze river from Shanghai. The brand name refers to Changzhou City, too. Changli = 常力. Changzhou = 常州. The character 力 means force, power, or strength, depending on context. So the best translation of the Changli name would be “Chang(zhou) Power.”

The Changzhou Changli Vehicle Factory recently opened a new factory, located in an industrial area in the far south of the city. The old factory was much closer to the center, but I guess there wasn’t enough space to expand there, and the building was really old. Check it out:

The Changzhou Changli Vehicle Factory is a subsidiary of a larger privately held company, called Changzhou Xili Vehicle Industry Co., Ltd. Confusingly, the Xili part of the name (喜力) is also the Chinese brand name of Dutch beer maker Heineken. Fortunately, not that many folks will confuse a small electric car for a bottle of delicious Dutch brew.

Changzhou Changli was founded in 1996 by a Mr. Yang Baocheng (杨保成). In the early days, the company only made tricycles. Later on, it added scooters and four-wheel cars to its fast-expanding lineup. The company’s main factory is in Changzhou, but it also operates factories in Chengdu, capital of Sichuan Province, and in the Tianjin Municipality. Changli operated a dealer and service network throughout China. According to the company’s website, it exports vehicles to countries and regions like Thailand, India, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Middle East. And, as we know, at least a few went to the United States.

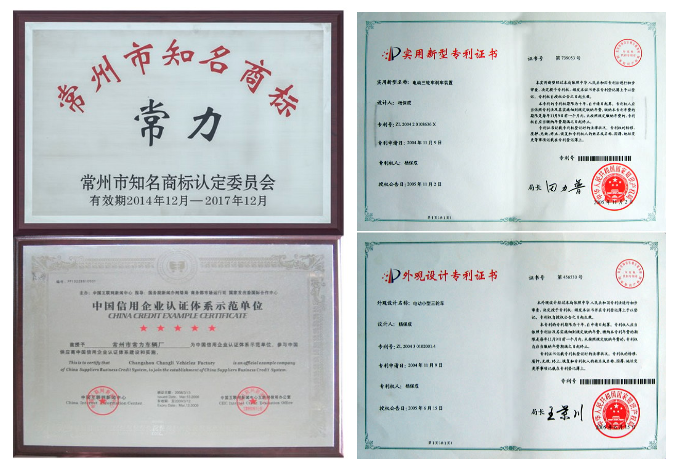

The company proudly talks about the many official certificates, titles, and honors it received from local governments and various branche organizations. These titles are not a necessity but they may make life easier when it comes to dealing with the government, for example for securing permits. Changzhou Changli holds, among many others, the titles for “Changzhou Well-known Trademark” and “Changzhou Private Technology Enterprise.” It is also a member of the “Jiangsu Bicycle Association.” The certificates are displayed on the website, with photographs showing the physical documents. This is a very common practice in China, especially among small and medium-sized companies.

In China, celebrity endorsements are very common among every kind of company, large and small. The selected celebrities are mostly Chinese but some are foreign. BAIC once had Nick Cage. Since 2017, Changli has an endorsement deal with Hong Kong actor Li Zixong (李子雄, Lee Chi Hung in Cantonese, Waise Lee in English). Images of Li, complete with his signature, are all over Changli’s website and shop. Li may be relatively unknown outside of China, but he is a famous fellow. Born in 1959, he starred in more than 100 movies. He is currently married to Chinese actress Wang Yaqi (王雅琦), who was born in 1982 and became famous after graduating from the People’s Liberation Army Academy of Arts.

Changli isn’t a very large company, not even by LSEV standards, where companies tend to be small compared to normal carmakers. Changli claims to employ 50 “senior technical personnel” and a total of some 200 employees. The company’s main product line is still the tricycle. The four wheeled cars are a secondary business. The tricycles come in all forms — roofed, without roof, box truck, flatbed, and many specialty vehicles.

I counted about 100 different cars, but the company’s Alibaba pages show even more. Besides those, Changli makes about a dozen four-wheel electric vehicles, two-dozen electric scooters, and two-dozen tricycles for the elderly. It’s a massive number of vehicles! Mr. Torchinsky’s Changli is no longer displayed on Changli’s official Chinese website. However, it is still shown on Changli’s English website and a listing in the company’s Alibaba shop, where the car sells for a cool $930.

Let’s have a quick look at some of Changli’s coolest four-wheel machines. Interestingly, the names of these cars differ depending on if you look at the company’s English or Chinese pages, and I don’t mean the obvious language difference. On the English pages, the cars only have their sales catalog names, with Mr. Torchinsky’s car being the CLZKC-002. That’s boring. Happily, the names on the Chinese site are much better. Jason’s car is named the “Freeman.”

All lovely little cars, and in China, none cost more than $1,200. So for just a few grand you can have a huge Changli LSEV collection.

The Way The Business Of Chinese LSEV-Production Works

One may wonder how a company with some 200 folks can make so many vehicles. Well, that’s because they don’t really make them. The LSEV manufacturing situation is somewhat comparable with gasoline car manufacturing in the 1990’s, like with the Cherokee XJ clones: A few larger car makers supplied platforms and engines to numerous smaller automakers, who assembled their own cars on top of that. With LSEVs it goes a step further, as smaller producers buy entire bodies, platforms, motors, and everything else from other manufacturers.

So most of these LSEV makers are actually mere LSEV assemblers. This means that the entry bar for the LSEV business is pretty low. At any moment, there are thousands of LSEV companies active, selling under tens of thousands of brands, sub-brands, and series. Companies start, go bankrupt, resurface, take over, merge, or simply disappear at a dizzying pace. This makes it great fun to follow, but it’s also just a frustrating marketplace — a company you did business with yesterday may be gone tomorrow, or have a different name, or belong to another business, or maybe it moved to another town. Happily, some companies live longer than others, and Changzhou Changli Vehicle Factory is one of those survivors.

The Body Builders

China has an endless number of body and part makers. For the LSEV industry, many are located in Shandong Province. Shandong is somewhat of a LSEV hotbed; many manufacturers are based there too, and once a year there is, or was, a fantastic LSEV show in the capital Jinan.

LSEV bodies are made of sheet metal (steel?) or plastic. The bodies are quite rough and often offered for sale out in the open on LSEV markets. Hopefully it won’t rain. Some LSEVs have plastic doors and body panels, others are made of plastic entirely. Like with everything in this business, there is huge variation.

Fresh from the factory, seen in the background.This is a sheet metal body shell for a four-door four-wheel car. Pics via a manufacturer based in Jining City, Shandong Province.

The bodies are welded together by hand. (Well, if it were a Rolls-Royce, we’d all praise the handmade traditions, wouldn’t we!). The whole thing is made so ready that it’s easy for the LSEV makers/assemblers to finish. It’s got all the holes in the right places, and present are the battery box that doubles as the base for the front seat, the bench for the rear seats, the doors, and the window frames.

This car shown has four doors and wheels too, but its design is of the modern sort. The “production line” is really a work station, where the body is welded and hammered together. (images via a manufacturer based in Dezhou City, Shandong Province). With suppliers like the ones offering the panels shown here, everyone can be an LSEV maker, and in a way, everybody is — especially down in Shandong.

Now let’s have a look at power. According to Changli’s specifications, Mr. Torchinsky’s car is powered by a motor with “Maximum Power(Ps): ≤100Ps Maximum Torque(Nm): ≤100 Nm”. That is totally true and at the same time totally useless information. Chinese sellers are often vague like this, afraid perhaps to scare good-willing customers away.

Changli’s Chinese site has more technical data, but not on Mr. Torchinsky’s car, as it isn’t on the site, and the pic on the English site goes to Alibaba. However, the vehicle closest in kind and size is the Changli New Freedom Light 2017 Style (常力新自由光2017款). This fine little machine is powered by an 48V or 60V 800 watt (1.1 horsepower) electric motor, powering the rear wheels. Other Changli cars have a similar output.

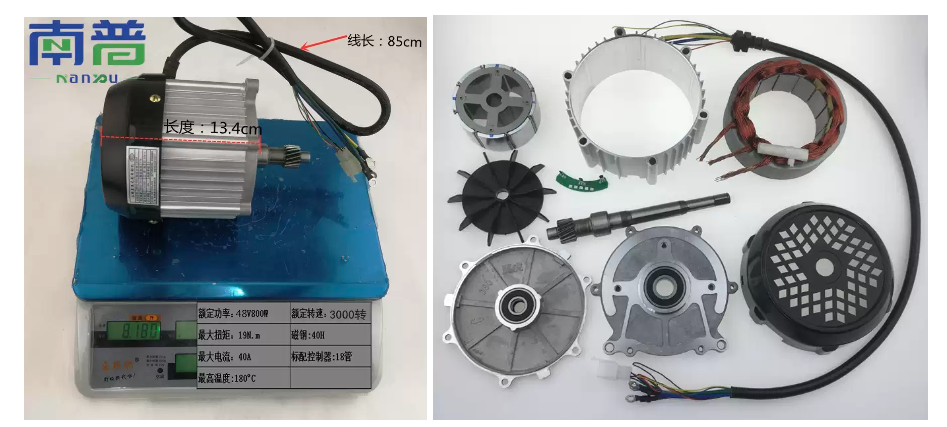

These little motors are very easy to get in China, with prices starting around 250 yuan (about $40). A typical example is the Nanyou 800W40, selling for 300 yuan. It’s a 48V motor with max output of 800W. Claimed power is 19 Nm. The motor unit is only 13.4 centimeters wide and comes with an 85 cm cable.

The sheer number of offerings is mind boggling. And every motor is available in many variants and sub-variants. For example, this is the Xixiangxi AA#384277923901. There are 24 base variants. Click on any model and you’ll get yet more choices. They’ve all got slightly different specifications. How does anyone make sense of this..? Prices start around 375 yuan (about $56).

This is how the electric motor is installed on a Changli tricycle. Bang on the rear axle, just like on Jason’s Changli!

So now we have a body and a motor. All we need is a battery. Batteries are the priciest part of any electric vehicle, and that goes for LSEVs as well. Until just a few years ago, all LSEV makers used old-school lead-acid units. Many still do, but they usually offer lithium-ion batteries as well, especially on higher-end vehicles. China being China, there are trillions of battery making companies, and many have their own celebrity endorsements.

The lead-acid batteries are super cheap. An example is this Tianneng 60V20AH (left), selling from 238 yuan ($36). They can be wired together for more output. In Beijing I had an electric scooter with five lead-acid batteries, it did 50 km/h and about 70 km of range. Lithium-ion batteries are incredibly cheap nowadays, however, they still cost way more than a basic lead-acid battery. The example on the right is a Weike 48V72V60, with a base price of 2300 yuan (~$350).

So we got the basics done: body, motor, and battery. All we need is some small stuff to finish the job.

Checklist: fan, dashboard, radio with horn, mirrors, grille with lights, interior door trim, and some fancy door handles. Add it all up and we got:

And that is the end of this story, for now. Hopefully, when Covid goes away, I can go to some LSEV shows again and tell you all about it. In the meantime, let’s hope Mr Torchinsky’s Changli keeps running as fine as it does today.

Terms

| 低速电动车 | Dīsù diàndòng chē | Low speed electric vehicle |

| 老头乐汽车 | Lǎotóu lè qìchē | A term for a category of small vehicles aimed at the elderly (lit: old man happy car). ICE or EV. |

| 常力 | Chánglì | Changli |

| 常州 | Chángzhōu | Changzhou |

| 电动车 | Diàndòng chē | Electric car (lit: electric moving car). |

| 常州市常力车辆厂 | Chángzhōu shì cháng lì chēliàng chǎng | Changzhou Changli Vehicle Factory |

| 常州市喜力车业有限公司 | Chángzhōu shì xǐ lì chē yè yǒuxiàn gōngsī | Changzhou Xili Vehicle Industry Co., Ltd. |

| 喜力 | Xǐ lì | Heineken |

| 喜力啤酒 | Xǐ lì píjiǔ | Heineken Beer |

| 老年休闲电动三轮车 | Lǎonián xiūxián diàndòng sānlúnchē | Elderly leisure electric tricycle |

| 电动四轮轿车 | Diàndòng sì lún jiàochē | Electric four-wheeled sedan. Term to describe four-wheel LSEVs. |

No one ever mistook Heineken for a delicious Dutch Beverage.

Question: When are Western dealers going to feature girls in bikinis grinding on poles in the salesroom? Asking for a friend.

Step 1: Buy a cheap and nasty LSEV body.

Step 2: Drop it on a Tesla chassis and do a bespoke luxury interior.

Step 3: Have fun.

What is the white single seat vehicle behind the stripper called?

With all the styles available, I’m surprised nobody has made a Fast and Furious spoof.

Hey, I loved the boomerang-eyed green one! What is its name?

As some others have mentioned I’m so impressed with the content on this site. This is fantastic stuff.

First of all I have been to Beijing. EVERYTHING there is a low speed vehicle. LOL

I did not realize the bodies were steel. I really thought they would be some sort of injection moulded plastic.

I think after COVID I will go over there to one of those shows and pick out my own selection of parts, ship them back and assemble my own bespoke EV. Or I guess I could order all of the parts on Alibaba and save a trip.

We should all go in on parts together… see if we can get an Autopian group rate.