I saw this graph earlier this year at a New York Auto Show marketing conference and it’s been haunting me ever since. I think it explains why the labor showdown isn’t getting resolved soon. I think it explains why automakers are losing their minds. I think it shows why everything in the automotive world feels so unsettled.

Also, I should note that I wasn’t invited to this conference (I don’t think) and definitely crashed it. The people who hosted it couldn’t have been more gracious and even fed me a sandwich, a cookie, and a Sprite. These are good people. I don’t remember much else about what was said at the conference, but this one graphic, from global intelligence firm S&P Mobility, has stuck with me.

I’m going to do a The Morning Dump wherein I just have one big story and a bunch of little ones sort of supporting it.

Term Of The Month: Peak Model Complexity

I’m grateful that the folks over at S&P have posted a related version of the graphic for us, in this story about Peak Model Complexity (PMC) and how it impacts marketing. They saw fit to make it an acronym and I agree. PMC! PMC! PMC! Get a tattoo of it on your left butt cheek now, thank me later.

I’m grateful that the folks over at S&P have posted a related version of the graphic for us, in this story about Peak Model Complexity (PMC) and how it impacts marketing. They saw fit to make it an acronym and I agree. PMC! PMC! PMC! Get a tattoo of it on your left butt cheek now, thank me later.

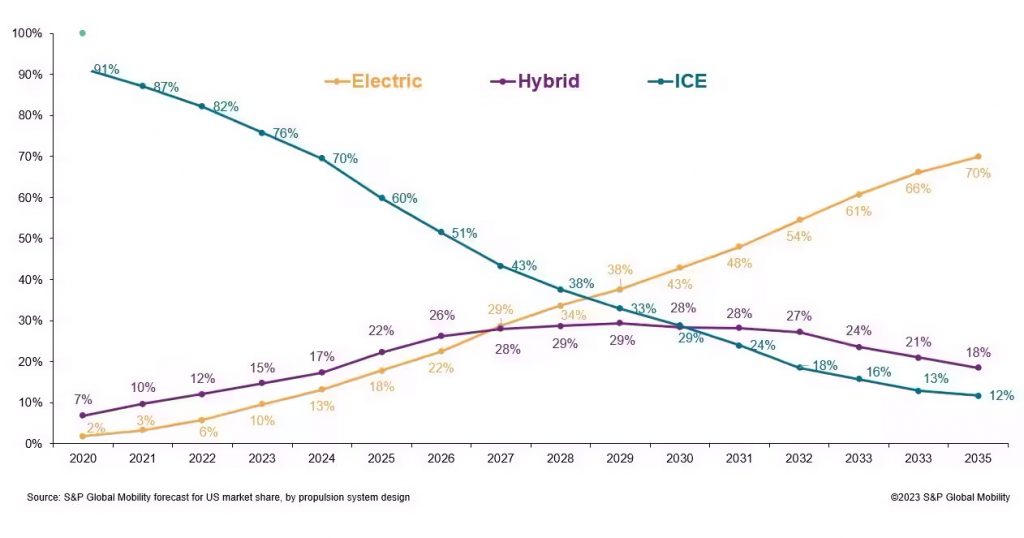

What the graph at the top of the post shows is that, right now, people in the United States have about 450 nameplates to consider when shopping for a car (this assumes Kia Niro PHEV, Kia Niro ICE, and Kia Niro EV are different models, but trim levels are the same). As car companies still sell their old gas model ranges and start incorporating EVs and PHEVs, there will be a crossover period where there are a lot of cars for sale. Somewhere in the 2027-2028 range, by S&P’s estimate, that number will rise to 650 nameplates.

In the graphic shown here, you get that not as total numbers of models, but as a percentage of the total market. If you look at the difference between the number of EV models and the actual percentage of vehicles that’ll actually be EVs you can start to see the issue. The number of gas models and pure BEV models reach parity around 2026, but they only crossover in terms of percentage of the market in 2028/2029.

Here’s S&P on what that all means, especially for marketing:

The increased model count will cause a drop in sales-per-nameplate figures: In 2018, the average sales volume per nameplate in the US market was 49,000 units. That is expected to dip to 36,000 by 2027. This requires some new thinking by OEMs, which for decades have stated that a nameplate must sell between 40,000 and 60,000 units to be profitable.

But this tectonic shift is happening already — impacting production cycles, sales forecasting, supplier relationships and marketing budget allocation.

The impact to profit margins, platform economics, operating expenses, product lifecycles and go-to-market timing will cut across all aspects of the auto business — from new and used car sales, to vehicle acquisition, parts and service. Retailers and their marketers will need to do more with less, and sooner than later.

Every marketing campaign and initiative will face this decision: Which message or offer should we serve to which customer — EV, hybrid, or ICE?

Marketing is definitely a key part of this and indicative of the larger problem, but the bolded parts are what I want to focus on. Just as I don’t think that automakers were particularly ready for the UAW strike, I question whether automakers (the ones that aren’t just pure EV automakers at least) are ready for all of this. The fact that automakers might be peeling back their EV ambitions in the face of slackening demand is yet another worrying factor because that’ll just lead to more model complexity.

This isn’t to say that automakers are blind to this. They aren’t. If you’re curious why the domestic automakers basically killed all of their cars, this is a big reason. They can only make so many cars and they’re already clearly going to be making so many cars.

Also, this assumes car sales are strong in 2027 and 2028. If the economy falters and car sales drop overall, the number of cars sold per unique model would be even lower than the 36,000 in 2027. Automakers need to make a lot of vehicles with big production numbers in order to be profitable, given the huge economies of scale that come with selling a million pickups as opposed to 30,000 small EV crossovers.

EVs, The Detroit 3, And The UAW

Electric vehicles have to be cheaper to make. Tesla’s huge advantage is only going to get bigger if Tesla, and other EV automakers, don’t have to worry about unionized labor, and don’t have to worry about dealers, and don’t have to worry about supporting millions of gas-powered cars at the same time.

Electric vehicles have to be cheaper to make. Tesla’s huge advantage is only going to get bigger if Tesla, and other EV automakers, don’t have to worry about unionized labor, and don’t have to worry about dealers, and don’t have to worry about supporting millions of gas-powered cars at the same time.

Automotive News has a piece that’s worth reading today about why the Detroit automakers (Ford, GM, Stellantis) rightly view the UAW strike as an existential issue, even if labor itself is only a small portion of the current costs associated with being an automaker:

“This is a defining period for Detroit and the future of the auto industry as we firmly believe that if GM, Ford, Stellantis accept anything close to the deal on the table the future will be very bleak for the U.S. auto industry,” Dan Ives, managing director at Wedbush Securities, said Wednesday in a research note to clients.

That’s a pretty bold statement, but here’s the thinking behind it:

If the Detroit 3 meet the UAW’s demands, labor costs would soar to $136 per employee, costing the companies up to $8 billion each, according to an analysis by Colin Langan with Wells Fargo. Taking a deal as it stands now would drive up the price of an EV by $3,000-$5,000, Wedbush estimates, at a time when new cars are already unaffordable to many and as automakers struggle to make money on EVs.

“This is … an almost impossible decision that could change the future of the Detroit automakers in our view,” Ives said. “Let’s be clear: This is a growing nightmare situation.”

Also, if you’re wondering why the current and former President decided it yuck it up with auto workers, this is why. Just three of the most important states to domestic automotive manufacturing (Michigan, Indiana, Ohio) are key to winning the White House.

This Is Why Ford And GM Are Hitting Back At The UAW

New strong statement from $GM CEO Mary Barra, echoing some remarks of here crosstown rival Farley: “We need the UAW leadership at the bargaining table with the clear intent of reaching an agreement now. For them to do otherwise is putting our collective future at stake.” pic.twitter.com/JCQZkxciFD

— Michael Wayland (@MikeWayland) September 29, 2023

The UAW strike is an ever-evolving situation and, frankly, as confused as automakers seem, I can’t promise that reporters are any smarter. The UAW is clearly, to me at least, using the media as much as they are using the automakers to tilt the negotiations towards themselves. It’s their right to do so, but it’s not a professional obligation for journalists to always fall for it (it’s possible that the UAW gave one outlet a fake strike plant list, for instance).

It has, at times, seemed like Ford and GM have done better than Stellantis, but it’s worth asking: Who wants us to think that? Is it the UAW? Is it the automakers?

Today, those two automakers and the UAW both pretty much agree that the other side is being unreasonable. Let’s start with GM CEO Mary Barra, whose statement is above, but here’s the key thing to me:

It is clear Shawn Fain wants to make history for himself, but it can’t be to the detriment of our represented team members in the industry. Serious bargaining happens at the table, not in public, with two parties who are willing to roll up their sleeves to get a deal done. The UAW is pitting the companies against one another, but it’s a strategy that only helps the non-union competition.

And, even harder from Ford CEO Jim Farley, via The Detroit Free Press:

“What’s really frustrating is that I believe we would’ve reached a compromise on pay and benefits but so far the UAW is holding the deal hostage over battery plants,” Farley said in extended remarks following a Facebook Live in which Fain announced the UAW’s next targets.

“Keep in mind, these battery plants don’t exist yet. They’re mostly joint ventures. They’ve not been organized by the UAW yet because workers haven’t been hired and won’t be for many years to come,” Farley said. “The UAW is scaring our workers by repeating something that is factually not true. None of our workers today are going to lose their jobs due to our battery plants during this contract period or even beyond this contract. In fact, for the foreseeable future, we will have to hire more workers as some workers retire, in order to keep up with the demand of our incredible new vehicles.”

He’s not entirely wrong. Those joint venture battery plants haven’t been built, they haven’t been organized, and Ford’s plans, in particular, are super in flux due to other serious issues. It’s not clear that Ford wants to, or can afford to, make all of those battery plants union plants. It’s interesting that Ford says he thinks the UAW has come to terms on benefits and pay (which explains the positivity last week) and, yet, can’t get past the battery thing.

It makes sense for the UAW to do what it can to sort of pre-organize the plants by guaranteeing higher wages for battery workers, but it also makes sense for automakers to point out that no one has even been hired for those plants!

Stellantis Suddenly Spared Strikes

Here’s a fun one. Stellantis has been mostly combative with the UAW, and vice versa, and yet Stellantis was spared another round of strikes. What’s going on here?

Here’s a fun one. Stellantis has been mostly combative with the UAW, and vice versa, and yet Stellantis was spared another round of strikes. What’s going on here?

Fain said Chrysler parent Stellantis was spared from additional strikes because of recent progress in negotiations with that company.

“Moments before this broadcast, Stellantis made significant progress on the 2009 cost-of-living allowance, the right not to cross a picket line, as well as the right to strike over product commitments and plant closures and outsourcing moratoriums,” said Fain, who was delayed nearly 30 minutes in making the online announcement. “We are excited about this momentum at Stellantis and hope it continues.”

As far as PMC is concerned, Stellantis is actually probably in better shape than Ford or GM. They’ve slowly starved their model lineups, with Chrysler basically becoming a brand of one and Dodge just barely offering cars themselves. People tend to point out the lack of products as a downside for Stellantis, and it currently is, but it opens up Stellantis to more opportunities and less PMC in the near term.

Also, curiously, it could make strike negotiations easier, because the company’s EV plans are a little fuzzier.

The Big Question

How big of a deal is PMC? What are other ways it can mess with the car market? Is it good for consumers or bad for consumers?

> The UAW is pitting the companies against one another

If I still had the capacity to be shocked by hypocrisy in corporate communications, I’d be shocked by how hypocritical this statement is.

There is exactly one way that propulsion system proportion chart becomes reality in 2035: we sell WAY WAY WAY less vehicles that year than we do now. Somewhere around 2027/2028 on that graph is when any change is going to hit a brick wall.

Subbed for this Dump. MH hit on something prescient that’s happening in many economic sectors the world over.

PMC a big deal? For auto, who knows? For auto, tech, and medicine – and the mining, transportation, and logistics that go with it – absolutely. The requirement that market performance driven “efficiency” and consolidation has left industry in a much less resilient state than in past generations. See also: COVID-induced supply chain disruptions.

Other impacts to the market? You mean other than erosion of the value of labor, cost of living crisis in the global west, and the inability to set policy, govern, and give industry clear targets for the future? No impact at all…

Good or bad for consumers? If current trends continue, we’ll be lucky to have a “consumer class” left to pontificate over.

Thought: how about not let name plates proliferate? That is 100% under the manufacturers’ control.

Make some name plates all electric, retire others, reduce duplication and badge engineered models.

You *have* to stake your claims for future jobs, otherwise you get reamed like artists did when streaming took over. Many of their contracts hadn’t anticipated streaming and didn’t carve out provisions to pay them for streamed content. So suddenly you wound up with media companies making $$ from licensing streaming content and not having to pay the talent.

Fain seems like a bit of a dick but he’s doing what he needs to do to avoid a repeat of 15 years ago.

Streaming has been complicated with some artists winning and some losing. But streaming is not what killed musician as a widespread career and transformed it into something where only a fraction of one percent succeed. That was the phonograph. Fain can insist on the big-3 paying for mediocre live performances, but unless he goes and smashes the phonographs at Toyota and Tesla (and is he really going to vandalize places where he possibly owns shares) it is just going to put the big-3 out of business. The restructuring 15 years ago is why there is a big-3 instead of a big-1 or a big-0.

Artists got “reamed” because they get paid over and over for work they did in the past. If we didn’t have an artificial government backed framework for monetizing past work, they’d have all had to go perform for money and the streamers wouldn’t have made any money either.

The rest of us have to keep working for a living.

As for the UAW, the world is short on unskilled labor. Seriously short. Anybody who can be replaced by a robot should be replaced by a robot, because we’ve got tons of work that robots can’t do yet that needs doing, and not enough of us out here to do it all. Society doesn’t need to help people lock themselves into obsolete jobs.

How’s the pay and (any) benefits?

A few years ago somebody on one of my other blogs was decrying the lack of labor for doing concrete work here in the SFBA. It took a while but I eventually got him to report a salary of $25 an hour with no benefits. Not much for one of the most expensive areas to live.

Today’s random conspiracy theory… Shawn Fain is on the take from the non-unionised auto makers, to keep the union plants production down for as long as possible, and make them less competitive in the longer term with a fat labour deal.

This is obviously entirely made up.

I have no evidence your theory is true, but all of his behavior is consistent with it being true.